(*1979, Melbourne, Australia)

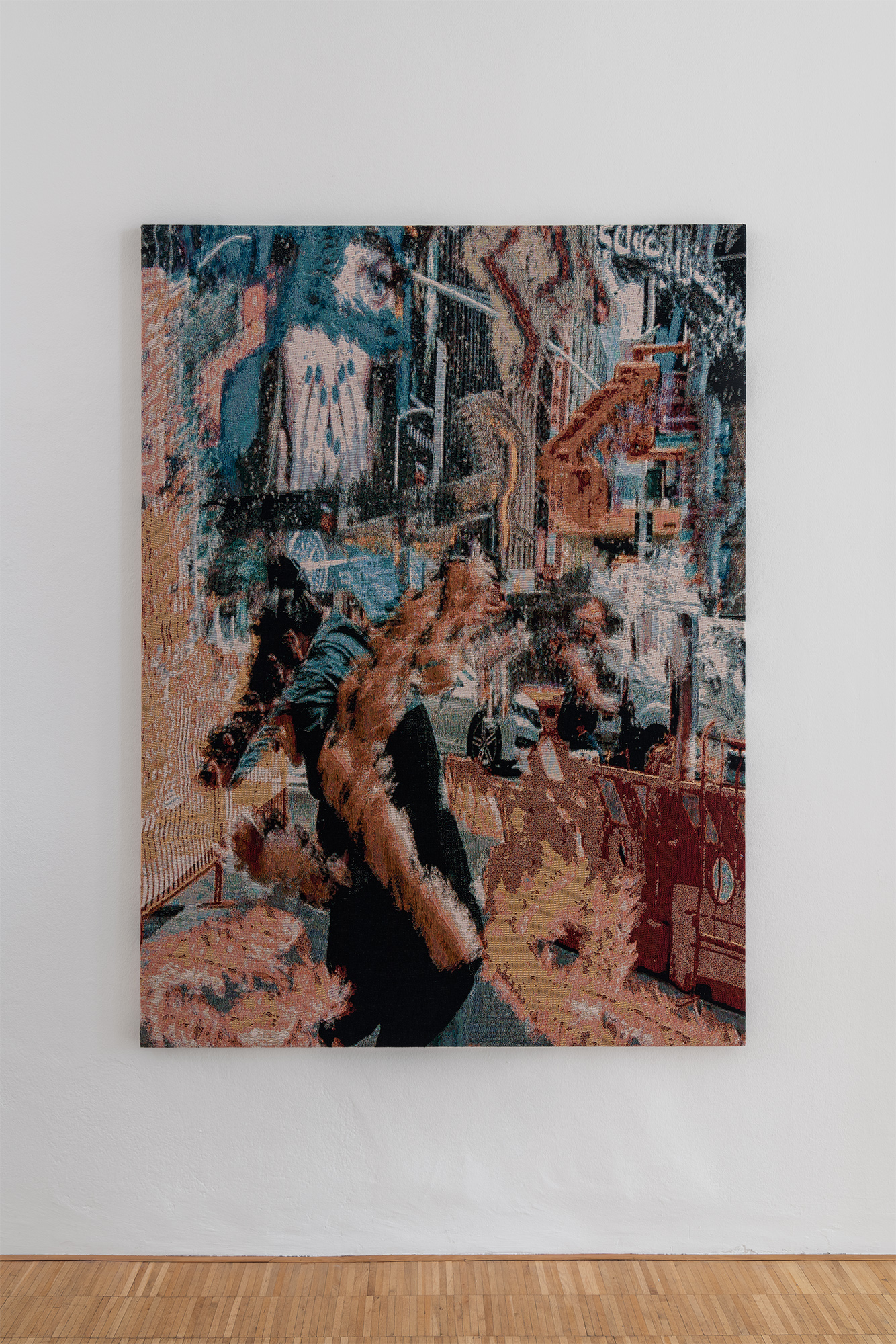

Ry David Bradley recognises the cyborg in us. His art operates as a collision of technologies; specifically, the intersection of a post-internet slippage of memory and texture at the precipice of the digital. Melting the pixel into the weft of both the handloom and the digitally operated jacquard loom, Bradley’s textile works reveal the clunky reality of algorithms and digitalisation. Scenes from digital life like social media, advertising and international news are made tactile yet fuzzy, furry and velvety, through a process of reproduction and remixing in a nod to the screen, the interface, to artifice, and back again to the history of painting. In transferring his images from the digital to the physical realm via textiles, Bradley renders his work immune to the obsolescence of hardware-reliant digital storage options, yet gives his work over to the natural changes and deterioration innate to fabric over time.

Ry David Bradley is represented by Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney and Last Resort, Copenhagen.

(*1979, Melbourne, Australien)

Ry David Bradley erkennt den Cyborg in uns. Seine Kunst operiert als ein Zusammenprall von Technologien, vor allem als ein Post-Internet-Ausgleiten der Erinnerung und der Textur am Abgrund des Digitalen. Indem er das Pixel sowohl mit dem Schussfaden des Handwebstuhls als auch mit dem des digital betriebenen Jacquardwebstuhls verschmilzt, legen Bradleys Textilarbeiten die klobige Wirklichkeit der Algorithmen und der Digitalisierung offen. Szenen aus dem digitalen Leben wie soziale Medien, Werbung und internationale Nachrichten werden durch einen Prozess der Reproduktion und des Remixing mit einem Hinweis auf den Bildschirm, die Schnittstelle, auf den Kunstgriff und wieder zurück auf die Geschichte der Malerei greifbar, doch zugleich flauschig, pelz- und samtartig gemacht. Indem er seine Bilder mittels Textilien aus dem digitalen in den physischen Bereich überträgt, immunisiert Bradley sein Werk gegen das Veralten von auf Hardware angewiesener digitaler Speicheroptionen, überantwortet sein Werk damit aber auch den natürlichen Veränderungen und dem Verfall, denen Stoff mit der Zeit ausgesetzt ist.

Ry David Bradley wird von Sullivan + Strumpf, Sydney, und Last Resort, Kopenhagen, vertreten.

(*1995, Berlin, Germany)

Elisa Breyer’s painting and textiles speak colourfully and ironically to the digital native generation she hails from. Her representations of knitted and woven textiles, found objects and motifs of now “retro” digital interfaces and technologies investigate the accelerated obsolescence of the digital era, playfully juxtaposing both hard and soft “wares”. Breyer’s paintings emphasise the tactile, intimate interiors and moments of her personal life, from innocuously intimate snapshots of friends, talisman-like detritus of sharehouse living, and intricately oil painted soft materials strewn in-and-over hard surfaces. These are moments behind moments; as if painted from a social media feed in the blurry, pixelated space between adulation and aestheticization synonymous with digital culture. Breyer’s work is a reminder of our need for IRL touch, softness, and for the kind of serotonin that “likes” don’t afford.

(*1995, Berlin, Deutschland)

Elisa Breyers Gemälde und Textilien sprechen auf farbenfrohe und ironische Weise die Generation der Digital Natives an, der sie selbst angehört. Ihre Darstellungen gestrickter und gewebter Textilien, gefundener Objekte und Motive der inzwischen »retro«-mäßigen digitalen Schnittstellen und Technologien untersuchen das beschleunigte Altern des digitalen Zeitalters und stellen harte und weiche »Waren« auf spielerische Weise nebeneinander. Breyers Gemälde betonen die taktilen, intimen Innenräume und Momente ihres Privatlebens, von unverfänglich unmittelbaren Schnappschüssen von Freundinnen und Freunden, talismanartigen Überbleibseln einer Sharehouse-Lebensweise und raffiniert in Öl gemalten Materialien, die in und über harte(n) Oberflächen verstreut herumliegen. Es sind die Momente hinter Momenten: als seien sie aus einem Social Media Feed in den unscharfen gepixelten Raum zwischen Bewunderung und Ästhetisierung hineingemalt, der mit der digitalen Kultur synonym ist. Breyers Werk erinnert uns an unser Bedürfnis nach echten, leibhaftigen Berührungen, Weichheit und jene Art Serotonin, das »Likes« (»Gefällt-mir«s) uns nicht bieten können.

(*1980, Sydney, Australia)

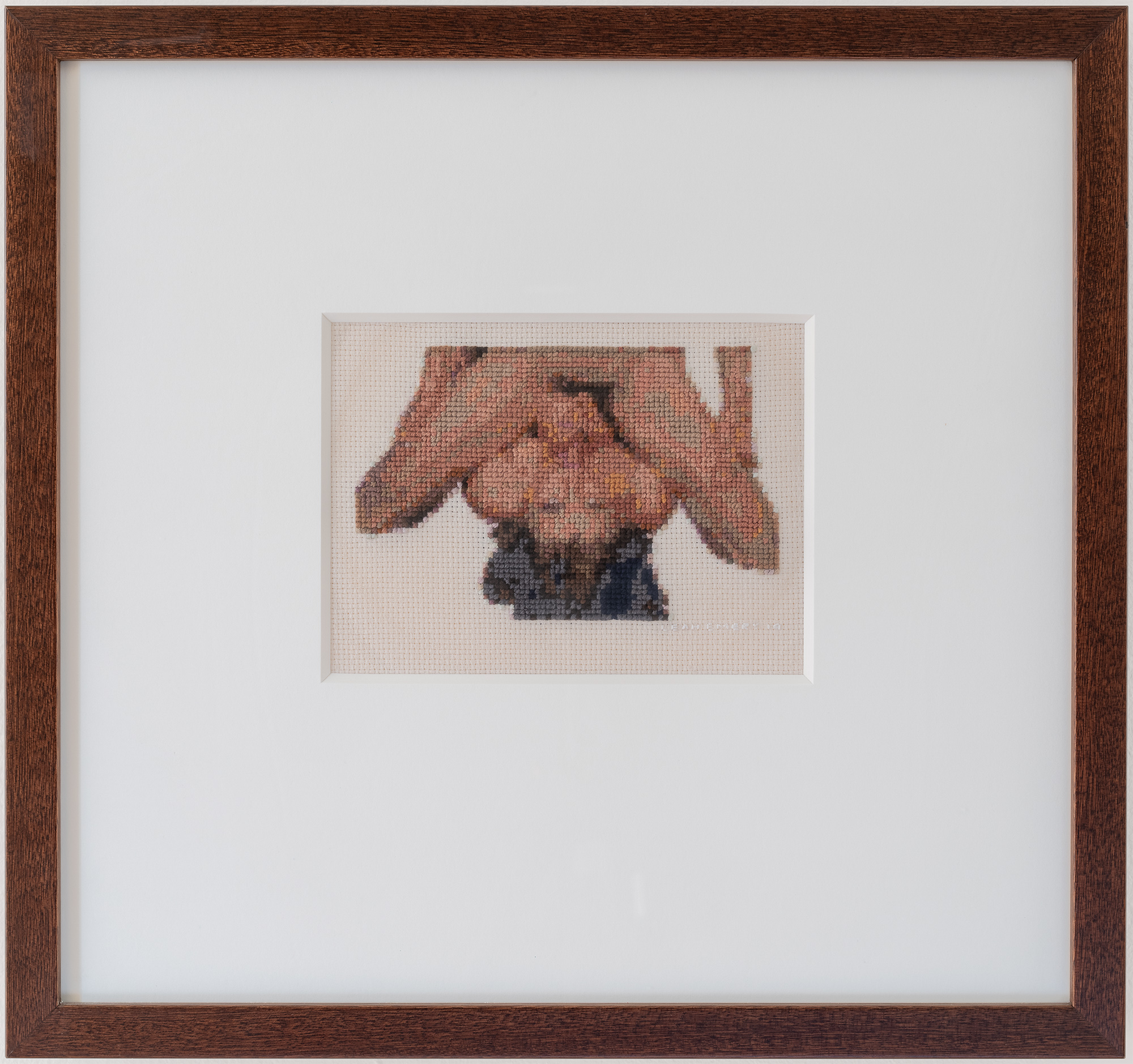

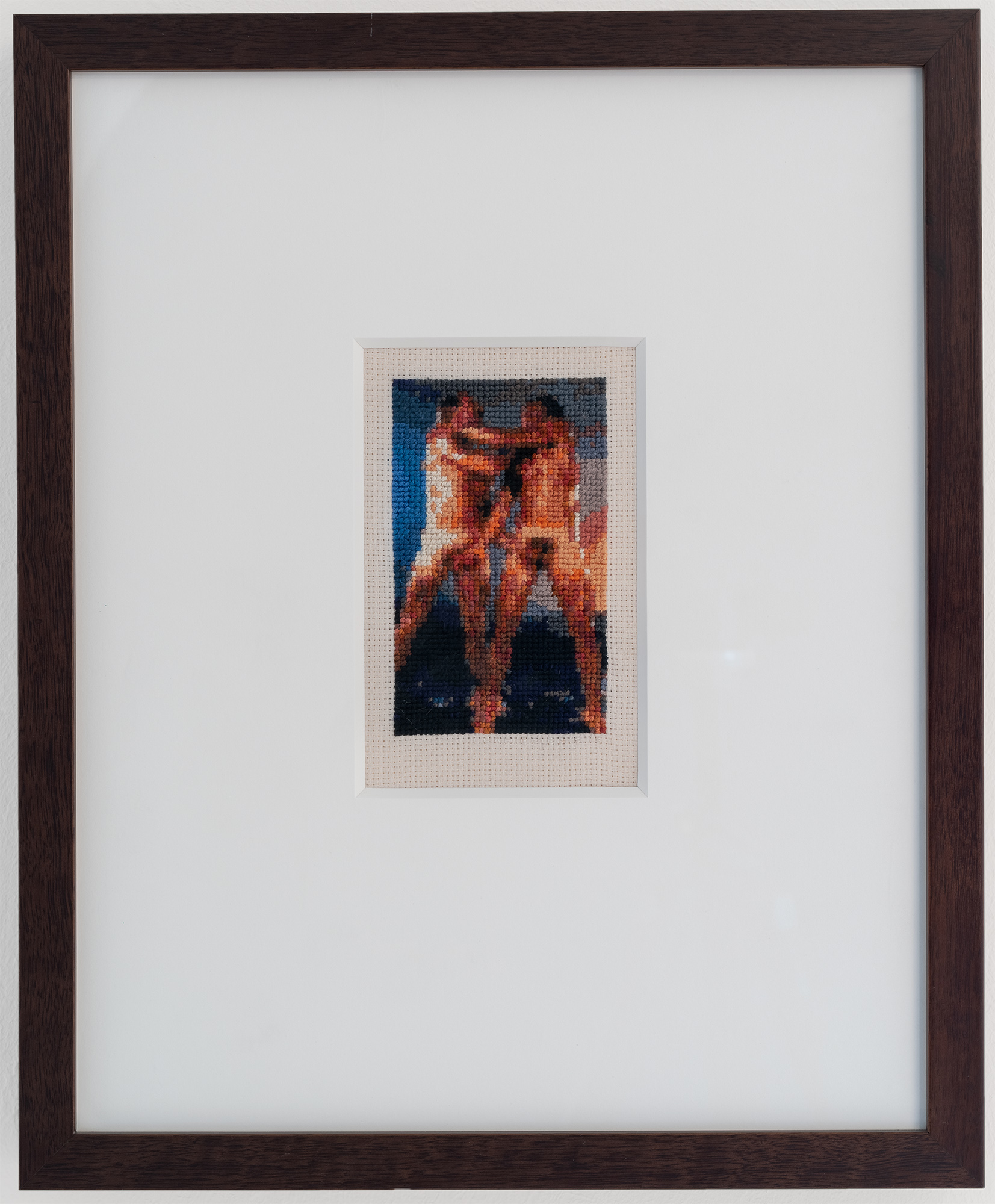

Leah Emery is a textile artist whose use of traditional embroidery techniques belies her subject matter in a fairly explicit manner. Known for embroidering stills from hard-core pornography, Emery’s scenes are voyeuristic and marked with contradictions – porn consumption is typically confined to the dark ether of the internet, rather than woven and materialised on a white background in careful, stitched relief. Resembling pixels, Emery’s fine cross-stitches make private internet activity and intimate gestures public through sometimes humorous, always confronting sexual poses and acts. Emery subverts the historically apolitical female domesticity signified by cross-stitch as a “women’s pastime”. Female activity is no longer relegated to the private realm of the home, nor is its subject matter benign. The artist brings pornography to light from the depths of the internet in an assertion of female agency.

Leah Emery is represented by Michael Reid, Berlin/Sydney.

(*1980, Sydney, Australien)

Leah Emery ist eine Textilkünstlerin, denen Stickereitechniken den Wiederspruch ihres Gegenstands entlarvt. Emery ist dafür bekannt Szenen aus Hardcore-Pornos zu sticken. Entsprechend sind ihre Motive voyeuristisch und durch Widersprüche gekennzeichnet. Der Pornokonsum beschränkt sich üblicherweise auf den dunklen Äther des Internets, statt in einem sorgfältigen gestickten Relief auf einen weißen Hintergrund gewebt und materialisiert zu sein. Emerys feine, an Pixel erinnernde Kreuzstiche machen die private Internetaktivität und intimen Gesten in manchmal humorvollen, stets aber konfrontativen sexuellen Posen und Akten öffentlich. Emery untergräbt die historisch apolitische weibliche Häuslichkeit, für die der Kreuzstich als »weiblicher Zeitvertreib« steht. Weibliche Aktivität ist hier nicht mehr in den privaten Bereich des Zuhauses verbannt und ihr Gegenstand nicht harmlos. Die Künstlerin holt Pornografie aus den Tiefen des Internets ans Licht und macht auf diese Weise weibliche Handlungsmacht geltend.

Leah Emery wird von Michael Reid, Berlin/Sydney vertreten.

(*1984, Tallinn, Estonia)

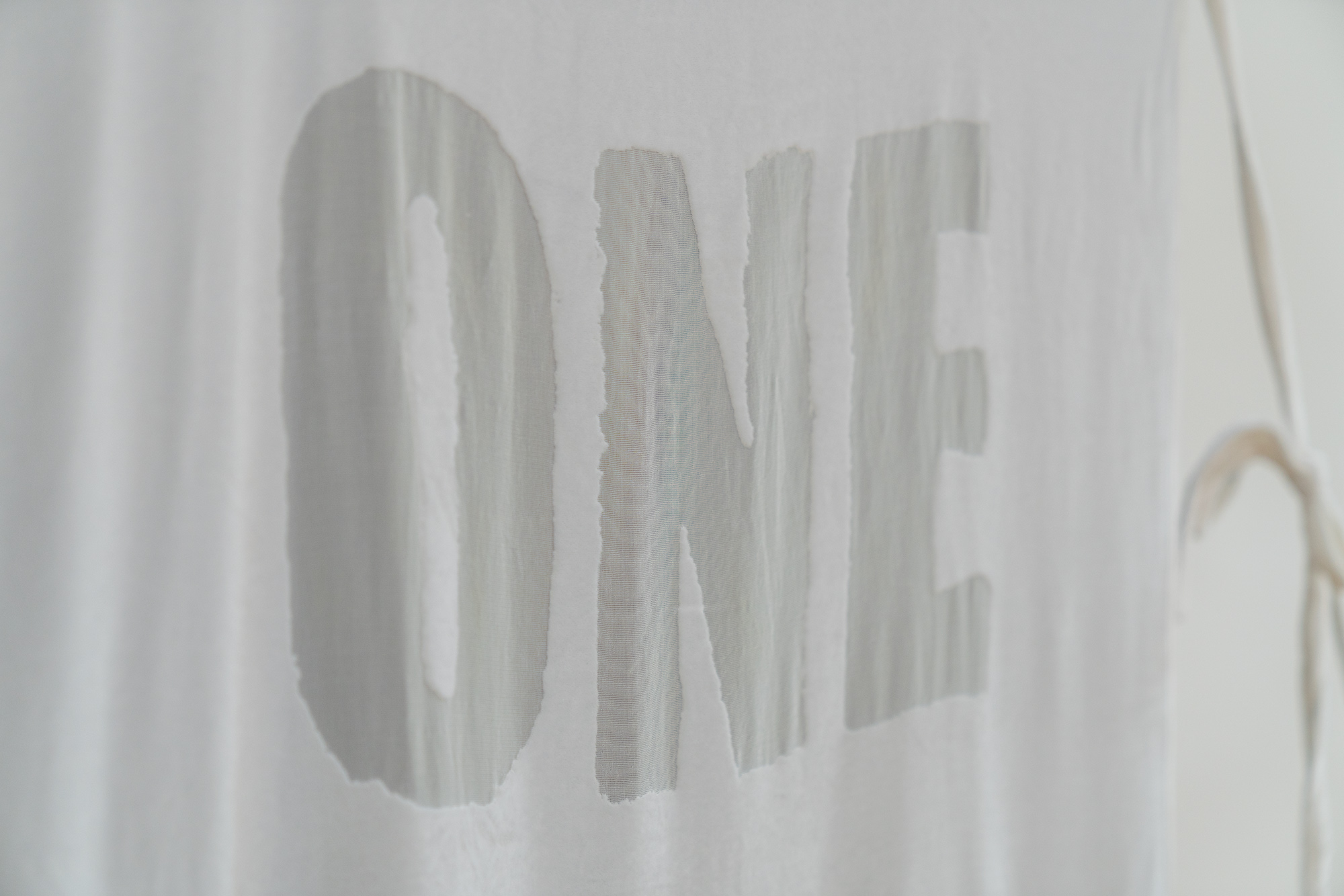

Sandra Kosorotova is an artist working primarily with text and textiles. Through a diverse range of community workshops, rituals and performances, her practice can be defined as a poetic mix of community service, fashion, activism, design and art. Drawing on traditionally domestic textiles and practices, Kosorotova reveals the healing and binding qualities of ritual and haptic performance in negotiating the soviet legacy and its complex diasporic elements. With works that ruminate on past and present collectivity and precarious modes of labour in contemporary life, Kosorotova works sensitively with a range of textiles and natural dye processes, using plants and flora from their local origin to bind people and place, culture and community. Kosorotova applies her poetic musings in large-scale text and textile works that raise awareness towards the precarity of work in post-capitalist society, class and identity politics, as well as economic uncertainty in the digital economy.

(*1984, Tallinn, Estland)

Sandra Kosorotova ist eine Künstlerin, die primär mit Texten und Textilien arbeitet. Durch eine große Bandbreite von Community-Workshops und Performances lässt sich ihre Praxis als eine poetische Mixtur aus gemeinnütziger Arbeit, Mode, Aktionismus, Design und Kunst definieren. Indem sie auf traditionell häusliche Textilien und Praktiken zurückgreift, offenbart Kosorotova die heilenden und bindenden Eigenschaften ritueller und haptischer Performance, indem sie das sowjetische Erbe und seine komplexen diasporischen Elemente verhandelt. Mit Werken, die über vergangene und gegenwärtige Kollektivität und prekäre Arbeitsweisen im zeitgenössischen Leben sinnieren, arbeitet Kosorotova auf sensible Weise mit einer großen Bandbreite von Textilien und natürlichen Färbeprozessen, wobei sie Pflanzen und Flora aus ihrem lokalen Ursprung benutzt, um Menschen und Ort, Kultur und Gemeinschaft miteinander zu verbinden. Kosorotova wendet ihre poetischen Grübeleien in großformatigen Text- und Textilarbeiten an, die das Bewusstsein für die Prekarität der Arbeit in der postkapitalistischen Gesellschaft, Klasse und Identitätspolitik sowie die wirtschaftliche Ungewissheit in der digitalen Ökonomie steigern.

(*1982, Schmalkalden, Germany)

Katrin Steiger is a conceptual artist working with textiles and multimedia, whose experimental work operates between observation and transformation to explore aspects of performativity in everyday life. With an interest in the visual signifiers of subcultures and a focus on utilitarian clothing such as sports and work wear and the uniform, Steiger inserts her body into her work as both “host” and site of production. Traditional textile techniques are re-employed, remixed and recontextualised in examining contemporary phenomena and behaviours. Steiger is also the founder of Textilwerkstatt – the textile workshop of the Bauhaus University Weimar and a site to experiment with textiles and fiber-based crafts.

(*1982, Schmalkalden, Deutschland)

Katrin Steiger ist eine Konzeptkünstlerin, die mit Textilien und Multimedia arbeitet und deren experimentelles Werk zwischen Beobachtung und Verwandlung operiert, um so Aspekte der Performativität im Alltagsleben zu erkunden. Mit ihrem Interesse an den visuellen Signifikanten und einem Fokus auf zweckmäßigen Kleidungsstücken wie Sport- und Arbeitskleidung sowie Uniformen bringt Steiger ihren Körper sowohl als »Wirt« wie auch als Produktionsstätte in ihr Werk ein. Traditionelle Textiltechniken werden eingesetzt, neu gemischt und in einen neuen Kontext gestellt. Dabei werden zeitgenössische Phänomene und Verhaltensweisen untersucht. Steiger ist auch die Gründerin der Textilwerkstatt der Bauhaus Universität Weimar, in der man – entsprechend der Tradition am Bauhaus Weimar – mit Textilien und textilfaserbasiertem Handwerk experimentieren kann.

(*1987, Melbourne, Australia)

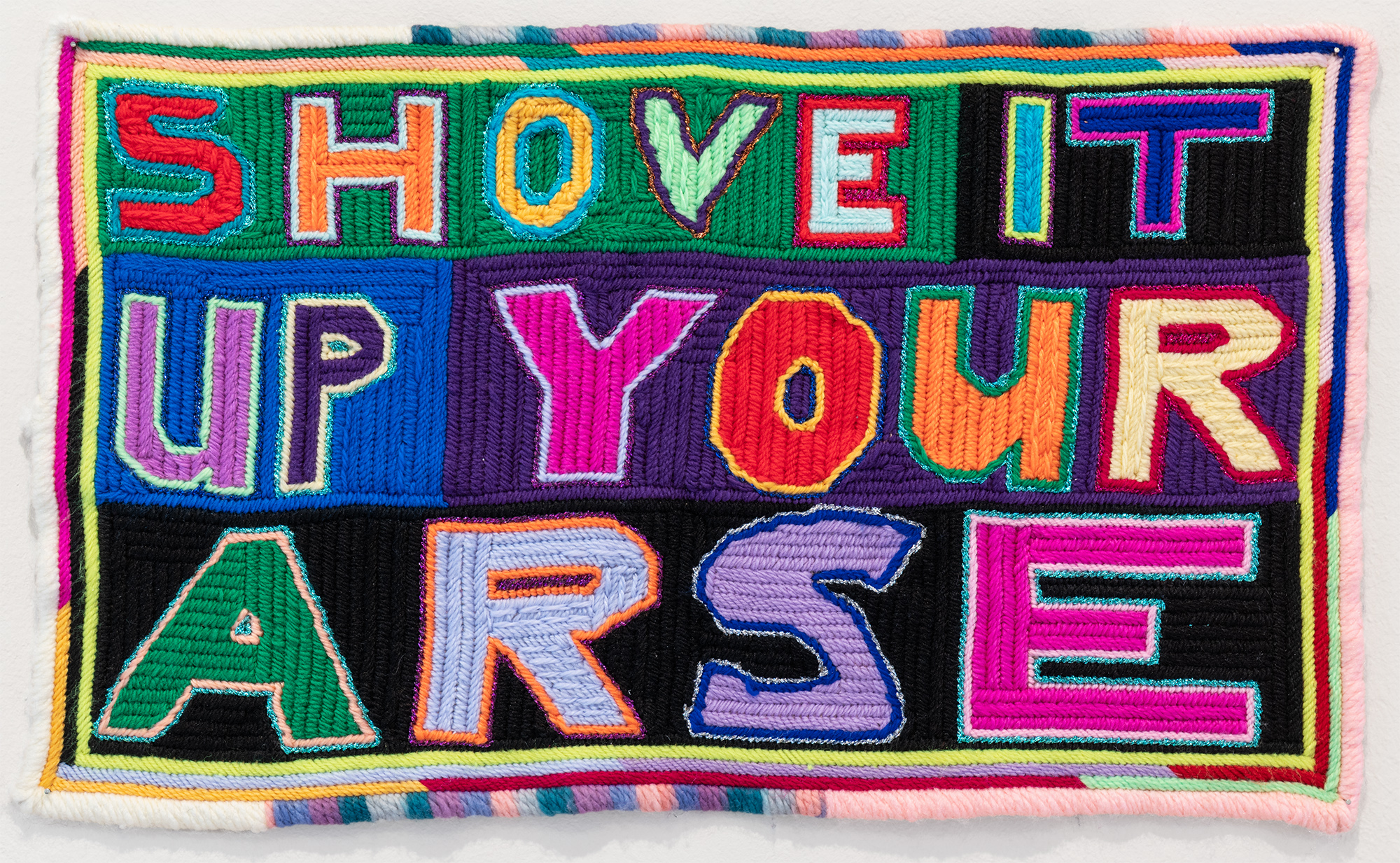

Paul Yore creates haptic melanges of socio-political associations using traditional textile methods. Meme-like humour and media-centric hyperbole are combined with a rainbow colour palette of fabric offcuts patched together that speak primarily to politicised queer and marginalised experiences. Yore’s quilted wall hangings and smaller needlepoint canvases comment on the disposability of contemporary and “other” cultures. By employing time-consuming handicraft methods, Yore forces a deceleration of the information deluge requisite of the internet age. The visual overload Yore’s work proffers is a tactile manifestation of inundating digital imagery, ironically intensified by the juxtaposition of its slow and highly considered process of creation.

Paul Yore is represented by Neon Parc, Melbourne and Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide.

(*1987, Melbourne, Australien)

Paul Yore bedient sich dabei traditioneller Textilmethoden und produziert haptische Melangen soziopolitischer Assoziationen: Meme-artiger Humor und medienzentrierte Übertreibung, die primär politisierte queere und marginalisierte Erfahrungen ansprechen, werden mit einer regenbogenfarben Palette aus zusammengefügten Stoffresten kombiniert. Diese quiltartigen Wandbehänge und kleineren Tapisserien kommentieren die Verfügbarkeit zeitgenössischer und »anderer« Kulturen. Durch den Einsatz zeitaufwendiger handwerklicher Methoden erzwingt der Künstler eine Entschleunigung der Informationsflut, die vom Internetzeitalter gefordert wird. Die uns von Yores Werk angebotene visuelle Überfrachtung ist eine taktile Manifestation der digitalen Bilderflut, die auf ironische Weise durch das Nebeneinander ihres langsamen und genau abgewogenen Schöpfungsprozesses intensiviert wird.

Paul Yore wird von Neon Parc, Melbourne, und Hugo Michell Gallery, Adelaide, vertreten.

(*1991, Pristina, Kosovo)

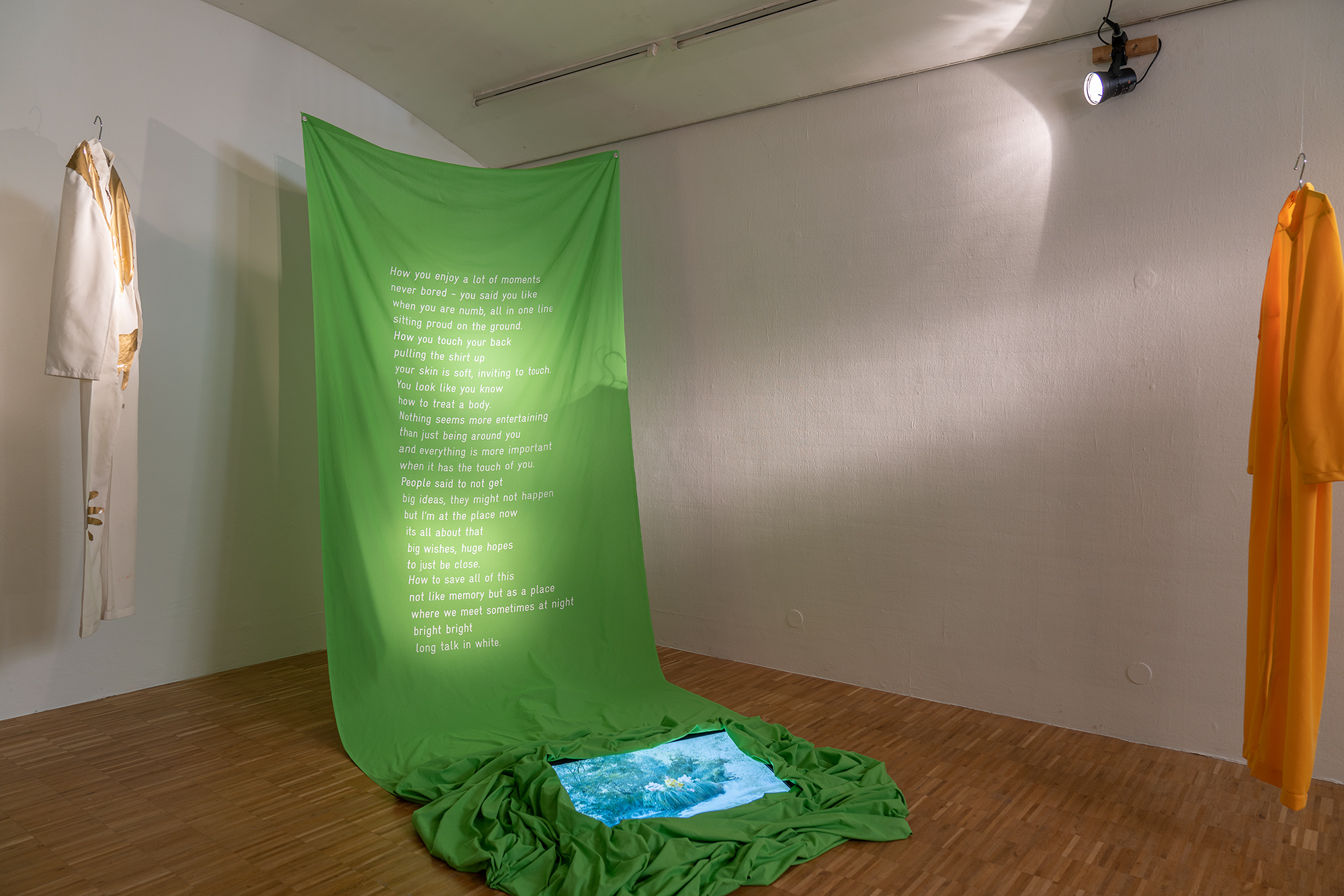

Kosovan artist Dardan Zhegrova draws from childhood experiences, customs and culture against the backdrop of the violent upheavals in the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Zhegrova works within the contemporary conflation of the private and public realm, self and other, and between both collective and individual intimacies – themes innately embedded in textile mediums. Role-play, imagination and the tactile in the post-digital largely figure in Zhegrova’s practice, which melds craft, drawing, puppetry, autofiction and performance, both physical and digital.

Dardan Zhegrova is represented by lambdalambdalambda, Pristina.

(*1991, Pristina, Kosovo)

Der kosovarische Künstler Dardan Zhegrova greift in seinem Werk auf die gewaltsamen Umwälzungen in der Sozialistischen Bundesrepublik Jugoslawien seine Kindheitserfahrungen, auf Gebräuche und auf Kultur im Allgemeinen zurück. Zhegrova arbeitet innerhalb der gegenwärtigen Verschmelzung des privaten und des öffentlichen Bereichs, des Selbst und des Anderen, und zwischen kollektiven und individuellen Intimitäten – Themen, die von Natur aus fester Bestandteil textiler Medien sind. Rollenspiel, Imagination und das Taktile im Post-digitalen spielen in Zhegrovas künstlerischer Praxis, die Handwerk, Zeichnung, Puppenspiel, Autofiktion und physische wie digitale Performance miteinander verschmilzen, eine große Rolle.

Dardan Zhegrova wird von lambdalambdalambda, Pristina, vertreten.

From soft to hard technologies and back again, textiles are not an oppositional force, but relative to the digital on a spectrum of textile tactility and digital intangibility. With a focus on touch and texture, Soft_Ware counters what the digital realm has widely forfeited.

This exhibition of international artists presents textile works engaging with hyperconsumerism, internet culture and the post-digital, and superseded technologies that have gained new resonance in our immaterial digital ether.

Seven millennial artists explore how and why the very medium that spawned the digital’s historical advent, textiles, so aptly serves as the post-digital medium and message to unpick it.

The digital mirroring of textile methods that underpin the concept and structure of the internet is refracted back from the virtual realm by young contemporary artists who have grown up parallel to its inception.

This exhibition is not the first to note that textiles have exploded in contemporary art. What it does ask is why textiles are the current medium of choice for artists to dissect the digital age.

Curated by Sarah Crowe

and David Ashley Kerr

Von weichen bis hin zu harten Technologien und wieder zurück, sind Textilien keine Gegenkraft, sondern befinden sich im Verhältnis zum Digitalen innerhalb eines Spektrums, zwischen textiler Tastbarkeit und digitaler Unberührbarkeit. Mit Fokus auf Berührung und Oberflächenbeschaffenheit tritt Soft_Ware dem entgegen, was die digitale Welt weitgehend aufgegeben hat.

Diese Ausstellung präsentiert Textilarbeiten internationaler Künstler/innen, in denen sie sich mit Hyperkonsum, Internetkultur und dem Post-digitalen befassen sowie mit überholten Technologien, die in unserem immateriellen digitalen Äther neue Resonanz finden.

Sieben Künstler/innen der Millennial-Generation erforschen, wie und warum gerade das Textilmedium, welches den historischen Einzug des Digitalen hervorbrachte, so passend als postdigitales Medium funktioniert und auch als Botschaft für dessen Entschlüsselung.

Es gibt eine Widerspiegelung von Textilmethoden im Digitalen; sie untermauern das Konzept und die Struktur des Internets und werden von jungen zeitgenössischen Künstler/innen, die parallel zu seiner Entstehung aufgewachsen sind, aus dem virtuellen Raum zurückgeholt.

Diese Ausstellung ist nicht die erste, die feststellt, dass Textilien in der zeitgenössischen Kunst explosionsartig an Bedeutung gewonnen haben. Sie stellt jedoch die Frage, warum Textilien zur Untersuchung des digitalen Zeitalters derzeit das Medium erster Wahl für Künstler/innen ist.

Kuratiert von Sarah Crowe

und David Ashley Kerr.

The similarities between textiles and digital technologies are uncannily pronounced. Parallels begin with their shared vocabulary: grid, network, web, thread. The genesis of digital terminology is the language of the loom. Thus, a return to this very apparatus, the loom as a symbol for textile craft, aids in grappling with the nature of an all-consuming digital existence, and digital technology comes full circle.

Textiles are marked with the human touch, much as tech is, through mistakes; older millennials encountered the early internet in all of its clunky, pixelated glory. Hard blocky interfaces have now been smoothed over, liquefied and bathed in a golden hour of pastel colours, as if this were the ideal of the future where we exist only in the cloud(s). Our fast fashion is interchangeable with the algorithm. We are almost one like away from our archetypal tropes, sold back to us in the form of clothing and accessories through targeted ads, as our meta-data is both mined and monetised.

That the punch card system used to work the machine-operated jacquard loom in the 1800s is regarded as the conceptual predecessor to computing technology is only a rather ironic textile/technology beginning. It stored its own information, functioned with its own software and dispersed the weavers’ centralised control throughout its hardware: “There was a good deal of resistance to the new loom (…) by workers who saw in this migration of control a piece of their bodies literally being transferred to the machine”.1

The term Future Looms2 was first coined by Sadie Plant during the early days of the internet to describe the omnipresence of technological systems underpinned by textile production. The works in Soft_Ware extend this concept into something akin to textile cybernetics. The pervasive power of an endless matrix of threads engulfing the digital body resurfaces in the physical realm as a dual form of both post-digital resistance and collective therapy.

We see it in the weave that is a bit off, the stitch that didn’t quite make it through; thread hanging out, we instinctively yank at it with the same impatience our finger stabs at a digital implement. As we sigh at Apple’s endless colour wheel of death or Microsoft’s infinite hourglass, it would do us well to remember that these are all marks, reminders of our fallible nature as humans, and our efforts in using technology to streamline our lives, make sense of the world, and define our place in it – metaphysical or otherwise. The link to textiles here may seem far-flung at first, but just as early textile cybernetics disrupted personal identities in the industrial age, millennial artists are now reclaiming textile practices to reinstate their own (humanly flawed) identities, relationships and connection to the world by subverting technological control through textile practices.

Meaning is both inscribed and derived through the inherent tactile nature of textiles as they forefront a post-digital consciousness in contemporary art, and with it, the increased technophoric3 turn. As television dies due to smooth, seamless online streaming, VR will eventually lose its hard edge and integrate into our lives like clothing – an apparatus of the every day, shrouding, veiling and shaping us and our bodies in both public and private realms. In acknowledgement of the soft female power of textiles and the community ethos it signifies, we remember Harlow’s monkeys4 in their attachment to their blankets and innate need for comfort and softness. Will hard tech be smooth enough to replace genuine touch and our tactile desire as creatures that need to come together for survival?

Soft_Ware counters what the digital realm has widely forfeited: touch and texture. It considers this turn to the digital, contemplating how textiles - marked by the touch of human error, laced with the scent of the human body, and inscribed with memories of the human experience – can usurp our techno-utopia one pierce of the sewing needle at a time.

September 2020.

-

Manuel Delanda, War in the Age of Intelligent Machines. New York: Zone Books, 1992, p. 168. ↩

-

Sadie Plant, The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics. Body & Society. 1995: 45-64. ↩

-

“Technophoria is a state of late capitalism that peddles the belief that our devices will satiate our needs and desires”. Omar Kholeif, Goodbye World! Looking at Art in the Digital Age. Berlin and New York: Sternberg Press, 2018, p. 89. ↩

-

American Psychologist Harry Harlow’s monkey studies in the 1950s probed psychological attachment in rhesus monkeys using methods of isolation and maternal deprivation. Harlow speculated that soft material could simulate the comfort provided by a mother’s touch and went on to design his now-famous surrogate mother experiment where soft textile stand-ins won over hard, wire alternatives, despite the latter also offering food. ↩

Textilien und digitale Technologien weisen ausgeprägte Gemeinsamkeiten auf, angefangen bei ihrem geteilten Vokabular: Grid (Netz), Network (Netzwerk), Web (Gewebe), Thread (Faden). Die Sprache des Webstuhls ist der Ursprung der digitalen Terminologie. Eine Rückbesinnung auf das Webgerät, wobei dieses als Symbol für das Textilhandwerk zu verstehen ist, ermöglicht die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Wesen einer alles bestimmenden digitalen Existenz – und digitale Technologie findet zu ihrem Ausgangspunkt zurück.

Textilien sind – ähnlich wie die Technologie – durch Fehler von Menschenhand geprägt; ältere Millennials erlebten noch das frühe Internet in seiner klobigen, pixeligen Pracht. Inzwischen wurden die hart blockigen Interfaces geglättet, aufgeweicht und sind in fast schon utopischer Manier glanzvoll illustriert, so als wäre dies das Ideal einer Zukunft, in der wir nur in der(den) Cloud(s) existieren. Unsere Fast Fashion ist durch den Algorithmus auswechselbar. Fast könnten wir mit dem nächsten Like unsere archetypischen Tropen verwirklichen; durch gezielte Werbung in Form von Kleidung und Accessoires werden sie an uns zurückverkauft, da unsere Metadaten sowohl gesammelt als auch monetarisiert werden.

Ein Lochkartensystem wurde im 19. Jahrhundert für den Betrieb des maschinengesteuerten Jacquardwebstuhl verwendet; dass dies als konzeptueller Vorläufer der Computertechnologie gilt, ist ein recht ironischer Textil/Technologie Einstieg. Das System speicherte eigene Informationen, funktionierte mit eigener Software und verteilte die zentralisierte Steuerung des Webers auf seine Hardware um: „Es gab erheblichen Widerstand gegen den neuen Webstuhl […] von Arbeitern, die durch die Abwanderung ihrer Kontrolle erlebten, wie ein Teil ihres Körpers förmlich in die Maschine verlagert wurde.”1

Der Begriff Future Looms2 (Webstühle der Zukunft) wurde erstmals von Sadie Plant während der Frühphase des Internets geprägt, um die Allgegenwärtigkeit technologischer Systeme zu beschreiben, die von der Textilproduktion untermauert werden. Die Arbeiten in der Ausstellung Soft_Ware erweitern diese Auffassung zu einer Art Textilkybernetik. Die tiefgreifende Kraft einer endlosen Matrix aus Threads (Fäden), welche die digitale Gesamtheit durchziehen, taucht in der physischen Welt wieder als duale Form postdigitalen Widerstands und kollektiver Therapie auf.

Man erkennt es an einem leicht fehlerhaften Gewebe, an einer Masche, die nicht ganz gelungen ist; kaum hängt ein Faden heraus, reißen wir instinktiv an diesem, und zwar mit derselben Ungeduld, mit der unser Finger auf ein digitales Gerät hämmert. Wenn Apples unaufhörlicher bunter Ball des Todes oder Microsofts unendliche Sanduhr einen zum Seufzen bringen, täte es gut, sich daran zu erinnern, dass dies alles Zeichen sind, Erinnerungen an unsere Fehlbarkeit als Menschen und an unsere Bemühungen, Technologie zur Optimierung unseres Lebens zu nutzen, um der Welt einen Sinn zu geben und unseren Platz in ihr zu definieren – ob metaphysisch oder sonstwie. Die Verknüpfung zu Textilien mag hier zunächst weit hergeholt erscheinen, aber ebenso wie die frühe Textilkybernetik im Industriezeitalter persönliche Identitäten zerrissen hat, greifen nun Künstler/innen der Millennial Generation in ihrer Praxis wieder zum Textilmedium; sie versuchen ihre eigenen (menschlichen) Identitäten, Beziehungen und ihre Verbundenheit mit der Welt wiederherzustellen, indem sie die technologische Kontrolle durch Textilpraktiken untergraben.

Die taktile Natur von Textilien birgt eine Bedeutung in sich, die ihr sowohl eingeschrieben ist als auch von ihr abgeleitet wird, da Textilien ein postdigitales Bewusstsein in der zeitgenössischen Kunst und damit den zunehmenden technophorischen3 Wandel vorantreiben. Während das Fernsehen aufgrund von reibungslosem Online-Streaming ausstirbt, wird VR schließlich seinen harten Charakter verlieren und sich wie Kleidung in unser Leben integrieren – ein Apparat des Alltags, der uns und unsere Körper sowohl im Öffentlichen als auch im Privaten verhüllt und formt. In Anerkennung der sanften weiblichen Seite von Textilien und des damit verbundenen Gemeinschaftsethos erinnern wir uns an Harlows Affen; 4 daran, wie sie an ihren Decken festhielten und damit ihr angeborenes Bedürfnis nach Geborgenheit und Weichheit ausdrückten. Wird harte Technologie sanft genug sein, um die echte Berührung und unser taktiles Verlangen als Geschöpfe, welche doch für das Überleben zusammenkommen müssen, zu ersetzen?

Mit Fokus auf Berührung und Oberflächen- beschaffenheit tritt Soft_Ware dem entgegen, was die digitale Welt weitgehend aufgegeben hat. Die Ausstellung betrachtet die Wende zum Digitalen, indem sie untersucht, wie Textilien – durch den Hauch menschlicher Fehler gekennzeichnet, mit dem Duft des menschlichen Körpers durchsetzt und mit Erinnerungen an die menschliche Erfahrungswelt behaftet unsere Techno-Utopie einen Nadelstich nach dem anderen erobern können.

September 2020.

Von Katerine Niedinger aus dem Englischen übersetzt.

-

Manuel Delanda. Englisches Originalzitat in War in the Age of Intelligent Machines, New York, Zone Books, 1992, S. 168. ↩

-

Sadie Plant. The Future Looms: Weaving Women and Cybernetics. In: Body & Society, 1995, S. 45-64. ↩

-

„Technophoria ist ein Zustand des Spätkapitalismus, der zur Annahme ermutigt, dass unsere Geräte unsere Bedürfnisse und Wünsche erfüllen werden.” Omar Kholeif. Englisches Originalzitat in Goodbye World! Looking at Art in the Digital Age, Berlin / New York, Sternberg Press, 2018, S. 89. ↩

-

Die Affenstudien von US-amerikanische Psychologe Harry Harlow untersuchten in den 1950er-Jahren die psychologische Bindung bei Rhesus-Äffchen mit Methoden der Isolation und des mütterlichen Entzugs. Harlow vermutete, dass weiches Material jene Geborgenheit simulieren könnte, die eine mütterliche Berührung mit sich bringt. Er entwarf daraufhin sein inzwischen berühmt gewordenes Experiment mit Ersatzmüttern, bei dem weiche Textil-Stellvertreter sich gegen harte Drahtalternativen durchsetzten, obgleich Letztere auch Nahrung anboten. ↩

From Jacquard Loom to Oculus Rift, weaving, the literal process of creation through connection, has long lended itself as a metaphor for technological advancement. In recent years, however, figures of fluidity seem to dominate the way we think about the digital. We’re surfing the stream rather than traversing the grid. In a 2019-published essay on Gina Beaver’s pastose, caked-on paintings, Naomi Fry describes her experience of revisiting Kim Kardashian’s sex tape over a decade after it first gained notoriety. What strikes her most about the footage is the pronounced visibility of texture: “the lace of her taupe-colored matching brassier-and-pantie set looks mall-coarse, itchy to the touch, her buttonish nipples emerging juttingly from the bra’s cups; even her pubic hair, groomed to within an inch of its life in a trendy early-2000s landing strip, appears bristly, tactile.” This profoundly palpable topography is at odds with the poreless and streamlined images of the Kardashians’ technomorphic bodies we are being confronted with today. Tactility, of course, hasn’t disappeared, but it has largely been washed away from the media landscape by the instantaneous receive-whilst-deliver logic of the stream. Long gone are the days of skeuomorph interfaces; today, the material imitates the virtual.

Inevitably, though, the textural comes back to haunt us. We feel it in the way the hot pink elastomeric nylon spandex fabric of the Fashion Nova mini dress reverse-engineered and mass-produced mere hours after Kim K was captured sporting a similar design in a paparazzi pic - clings to our skin.

Nowhere does the bulimic nature of online consumer culture become as palpable as in the repulsively soft fabrics of our impulse online purchases that transpire nauseating and most likely carcinogenic fumes as soon as we unleash them from their cardboard packaging. Similar to how the handiwork of the nuclear family housewife seeps away into mended holes and straightened hemlines, only becoming visible in negligent or purposefully disruptive knitting flaws, tactile fabrics mostly enter our post-digital field of perception as sources of undesired friction. Vandalism might be a gut reaction to the visceral impact such textiles have on us: desecrate the heartthrob idols’ prepubescent smooth faces printed onto wrinkle-free bed sheets; Fontana slash the fleece horse-motif blanket to uncover the infinite emptiness lying behind. But blind rage is not the response that sudorific lycra, satiny viscose and piercing sequins call for. Much rather, they serve as a reminder of a truth once uttered by Bauhaus pioneer Anni Albers: “We must come down to earth from the clouds where we live in vagueness, and experience the most real thing there is: material.”1

Albers, in her decidedly artistic approach to the ancient craft of weaving, claimed a hands-on agency over the materials that surround us so intimately in our everyday life. She chose the loom, site of both industrialisation and anticapitalist resistance, as an instrument to counteract the alienating effects of the wage labor system. Textile as a transitive verb, stemming from the same Latin texere – to weave – as texture: “to give texture, to refuse easy binaries, to acknowledge complications.”2 Albers is part of a great web of artists, only a fraction of them acknowledged by the writings of history, who embrace fabric’s ability to fold, wrap, absorb and wear. I think of Faith Ringgold, whose narrative quilts allow images of marginalised yet triumphant African-American quotidian life to travel outside the well-trodden paths art usually circulates on; of Vivian Suter, who allows her canvas cloth to be permeated by microorganisms and volcanic matter.

These artists embrace fabric qualities all too often condemned as acratic. They make use of the benefits that, as Sara Ahmed reminds us, being overlooked brings about: “to have more room to roam, to vary, to deviate; to proliferate.” Making queer use of fabric: looming subway wall tags and throw-ups into tapestries, installing exhibits with safety pins, allowing for the late summer breeze entering through the door to gently sway them around. Textile art snuggles up to the smooth, described by Deleuze and Guattari thus: “not […] homogeneous, quite the contrary: […] an amorphous, nonformal space.”3 Let us return to the metaphorical realms of the web. What does it mean to insist on the symbolism of the loom, to render it palpable by creating pliant replica of pixels through the intersection of warp and weft? In a cyberspace dominated by corporate interests, it urges us to swim upstream, or better yet, to leave the shipping routes altogether; to return to the loom and create haptic patchworks from smooth, chunky threads.

September 2020.

Vom Jacquardwebstuhl zur Oculus Rift: Das Weben, der regelrechte Prozess der Erschaffung durch Verbindung, bietet sich seit langem als Metapher für den technologischen Fortschritt an. Doch in den letzten Jahren scheinen Figuren der Fluidität die Denkweise über das Digitale zu dominieren. Wir surfen den Stream, anstatt das Grid (Netz) zu durchqueren. In einem 2019 veröffentlichten Essay über Gina Beavers pastose Gemälde beschreibt Naomi Fry ihre Eindrücke, als sie Kim Kardashians Sextape über ein Jahrzehnt, nachdem es zum ersten Mal bekannt geworden war, erneut auf sich wirken ließ. Was ihr an dem Videomaterial am meisten auffällt, ist die ausgeprägte Sichtbarkeit von Textur: „Die Spitze ihres taupefarbenen, zueinander passenden Büstenhalter- und Höschensets sieht rau aus wie frisch aus dem Kaufhaus, kratzig auf der Haut, wobei ihre knopfförmigen Brustwarzen aus den Körbchen des BHs hervortreten; sogar ihr Schamhaar, das bis auf wenige Zentimeter zu einer Landebahn frisiert wurde, wie es Anfang der 2000er-Jahre trendy war, wirkt borstig und taktil.” Diese ungemein tastbare Topografie steht im Widerspruch zu den porenlosen und gestrafften Abbildungen der technomorphen Körper der Kardashians, wie sie uns heute präsentiert werden. Die Taktilität ist natürlich nicht verschwunden, doch die unmittelbare, bereits im Zuge der Übertragung abspielende Logik des Streams hat sie weitgehend aus der Medienlandschaft weggespült. Längst vorbei sind die Zeiten skeuomorpher Interfaces; heute imitiert das Materielle das Virtuelle.

Und doch verfolgt uns die Beschaffenheit von Material unweigerlich aufs Neue. Wir spüren förmlich wie das knallpinke, elastomere Nylon-Spandex-Gewebe des Fashion Nova Minikleids, das nur wenige Stunden, nachdem Kim K. mit einem ähnlichen Design auf einem Paparazzi-Bild zu sehen war, nachkonstruiert und massenproduziert wurde, an unserer Haut haftet.

Nirgendwo wird die bulimische Natur der Online-Konsumkultur so greifbar wie in den abstoßend weichen Stoffen unserer Online-Impulskäufe, welche ekelerregende und höchstwahrscheinlich krebserregende Dämpfe ausstoßen, sobald wir sie aus ihren Kartonverpackungen befreien. Ähnlich wie die Handarbeit der Kernfamilien-Hausfrau in geflickte Löcher und gerade gezogene Säume versickert und nur durch fahrlässige oder absichtlich störende Strickfehler sichtbar wird, gelangen taktile Stoffe meist als Auslöser unerwünschter Friktion in unser postdigitales Wahrnehmungsfeld. Vandalismus ist eine mögliche, instinktive Reaktion auf die Wirkung solcher Textilien auf uns: Entweiht die auf faltenfreie Bettlaken gedruckten vorpubertären, glatten Gesichter der Teenie-Idole; Fontana-schlitzt die Vliesdecke mit Pferdemotiven auf, um die unendliche Leere, die dahinter liegt, zu enthüllen. Aber blinde Wut ist nicht die Antwort, die schweißtreibendes Lycra, seidige Viskose und stechende Pailletten verlangen. Vielmehr erinnern sie uns an eine einst von der Bauhaus-Pionierin Anni Albers formulierte Wahrheit: „Wir müssen von den Wolken, wo wir im Vagen leben, auf die Erde herunterkommen und das Wirklichste erleben, was es gibt: Material.”1

In ihrer entschieden künstlerischen Annäherung an das uralte Handwerk des Webens beanspruchte Albers eine praktische Auseinandersetzung mit den Materialien, die uns in unserem Alltagsleben so intim umgeben. Sie wählte den Webstuhl, Austragungspunkt sowohl der Industrialisierung als auch des antikapitalistischen Widerstands, als ein Instrument, um den Verfremdungseffekten der Lohnarbeit entgegenzuwirken. Textil als transitives Verb, stammend vom gleichen lateinischen texere – weben – wie Textur: „Textur geben, einfache Binärpaare ablehnen, Komplikationen anerkennen.”2

Albers gehört zu einem großen Geflecht aus Künstler/innen, von denen nur ein Bruchteil in der Geschichtsschreibung anerkannt ist, die Faltbarkeit, Wickelbarkeit, Absorbtion und Abnutzung des Stoffs zu schätzen wissen und nutzen. Ich denke hier an Faith Ringgold, deren narrative Quilts Bilder des marginalisierten und doch triumphalen afroamerikanischen Alltagslebens abseits der ausgetretenen Pfade der Kunst in Umlauf bringen; oder an Vivian Suter, die es zulässt, dass ihr Leinwandtuch von Mikroorganismen und vulkanischer Materie durchdrungen wird.

Diese Künstler/innen begrüßen jene Stoffqualitäten, die allzu oft als akratisch verurteilt werden. Sie machen sich jene Vorteile zunutze, die, wie Sara Ahmed uns erinnert, das Übersehen-Werden mit sich bringt: „mehr Raum haben zum Stöbern, zum Variieren, zum Abweichen; zum Verbreiten.” Stoffe auf queere Art und Weise nutzen: Tags und Throw-Ups von U-Bahn-Wänden in Tapisserien verweben, Exponate mit Sicherheitsnadeln befestigen, sodass die spätsommerliche Brise durch die Tür eindringen und sie sanft hin und her wiegen kann. Die Textilkunst schmiegt sich an das Glatte, das Deleuze und Guattari beschreiben als: „nicht homogen […], ganz im Gegenteil: […] ein amorpher, informeller Raum.”3

Kehren wir zu den metaphorischen Gefilden des Netzes zurück. Was bedeutet es, auf die Symbolkraft des Webstuhls zu bestehen und dies durch die Erzeugung gefügiger Replikas aus Pixel durch die Kreuzung von Kettfaden und Schussfaden greifbar zu machen? In einem von Unternehmensinteressen dominierten Cyberspace werden wir dazu aufgefordert, stromaufwärts zu schwimmen, oder besser noch, die Schifffahrtswege ganz zu verlassen; und stattdessen zum Webstuhl zurückzukehren und haptische Patchworks aus weichen, klobigen Fäden zu schaffen.

September 2020.

Von Katerine Niedinger aus dem Englischen übersetzt.

Katrin Steiger, ALE, 2020, wool and linen, handwoven, 200 x 93 cm, courtesy the artist

Paul Yore, Mother Tongue, 2017, mixed media textile, beads, buttons, sequins, acrylic, enamel, watercolour, found objects, 348 x 212 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Sandra Kosorotova, To Be A One At All You Must Be A Many (detail), 2018, fabric, devoré (burnout), dimensions variable, courtesy the artist

Sandra Kosorotova, To Be A One At All You Must Be A Many (detail), 2018, fabric, devoré (burnout), dimensions variable, courtesy the artist

Sandra Kosorotova, To Be A One At All You Must Be A Many, 2018, fabric, devoré (burnout), dimensions variable, courtesy the artist

Ry David Bradley, Tuq1_, 2018, 180cm x 140 cm, dye cotton tapestry, courtesy the artist and The Hole, New York

Dardan Zhegrova, Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Pink), 2017, mixed media and sound, approx. 200 x 100 cm, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Dardan Zhegrova, Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Gold), 2017, and Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Blue), 2017, each mixed media and sound, approx. 200 x 100 cm, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Dardan Zhegrova, Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Blue), 2017, mixed media and sound, approx. 200 x 100 cm, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Katrin Steiger, nose, 2020, salt-dough clay, acrylic paint, red string, dinemsions variable, courtesy the artist

Katrin Steiger, SMILE , 2020, print on silk/cotton, 203 x 130 cm, and nose, 2020, salt-dough clay, acrylic paint, red string, courtesy the artist

Installation view, Soft_Ware, Kunsthaus Erfurt 2020, with Paul Yore, SHOVE IT UP YOUR ARSE, 2017, wool needlepoint, 48 x 28 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin; and Leah Emery, Bodies of Evidence #7, 2015, 12.5 x 16.5 cm, Bodies of Evidence #5, 2014, 15 x 9.5 cm, and Bodies of Evidence #8, 2014, 19.5 x 13 cm, all embroidery thread on aida cloth, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Paul Yore, SHOVE IT UP YOUR ARSE, 2017, wool needlepoint, 48 x 28 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Leah Emery, Bodies of Evidence #5, 2014, embroidery thread on aida cloth, 15 x 9.5 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Leah Emery, Bodies of Evidence #6, 2014, embroidery thread on aida cloth, 19 x 12 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Paul Yore, NOTHING, 2016, mixed media textile appliqué including found materials, wool, beads, sequins, buttons, acrylic paint, 201 x 202 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Ry David Bradley, _rOS3, 8A*wU, and 7!DeN, all 2020, dye transfer on velvet, 120 x 160 cm, courtesy the artist and The Hole, New York

Elisa Breyer, to be good or to be good at it, 2020, PVC, heat packs, mannequin, framed photograph, dimensions variable, and UNTITLED_PAIN, 2018, crocheted wool, 100 x 110 cm, courtesy the artist

Elisa Breyer, UNTITLED_PAIN, 2018, crocheted wool, 100 x 110 cm, courtesy the artist

Elisa Breyer, to be good or to be good at it (detail), 2020, PVC, heat packs, mannequin, framed photograph, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist

Paul Yore, DREAMING IS FREE, 2016, wool needlepoint, 43 x 34 cm, courtesy the artist and Michael Reid, Berlin

Dardan Zhegrova, Brown, 2015/2020, White, 2015, and Yellow, 2015, all fabric, 180 x 40 cm; SAME, 2020, screenprint on Chromakey fabric, 150 x 350 cm; and I should begin telling you how I feel, 2015, HD-Film, 04’34” in collaboration with Samuel Weniger; courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Dardan Zhegrova, White, 2015, and Yellow, 2015, both fabric, 180 x 40 cm; SAME, 2020, screenprint on Chromakey fabric, 150 x 350 cm; and I should begin telling you how I feel, 2015, HD-Film, 04’34” in collaboration with Samuel Weniger; courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Katrin Steiger, OBI, 2020, print on linen, 291 x 135 cm, courtesy the artist

Sandra Kosorotova, To Be A One At All You Must Be A Many (detail), 2018, fabric, devoré, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist

Dardan Zhegrova, Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Pink), 2017, Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Gold), 2017, and Your enthusiasm to tell a story (Blue), 2017, all mixed media and sound, approx. 200 x 100 cm, dimensions variable, courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Ry David Bradley, 7!DeN (detail), 2020, dye transfer on velvet, 120 x 160 cm, courtesy the artist and The Hole, New York

Dardan Zhegrova, I should begin telling you how I feel, 2015, HD-Film, 04’34” in collaboration with Samuel Weniger; courtesy the artist and LambdaLambdaLambda, Prishtina

Install views of Soft_Ware, Kunsthaus Erfurt 2020. All photos and footage: Marcus Glahn.

Installationsansichten von Soft_Ware, Kunsthaus Erfurt 2020. Alle Fotos und Videomaterial: Marcus Glahn.